The Night of Terror: When Suffragists Were Imprisoned and Tortured in 1917

Dorothy Day was described by her fellow suffragists as a “frail girl.” Yet on the night of November 14, 1917, prison guards at the Occoquan Workhouse, did not hold back after she and 32 other women had been arrested several days earlier for picketing outside the White House.

“The two men handling her were twisting her arms above her head. Then suddenly they lifted her up and banged her down over the arm of an iron bench—twice,” recalled 73-year-old Mary Nolan, the oldest of the prisoners, in an account published by Doris Stevens.

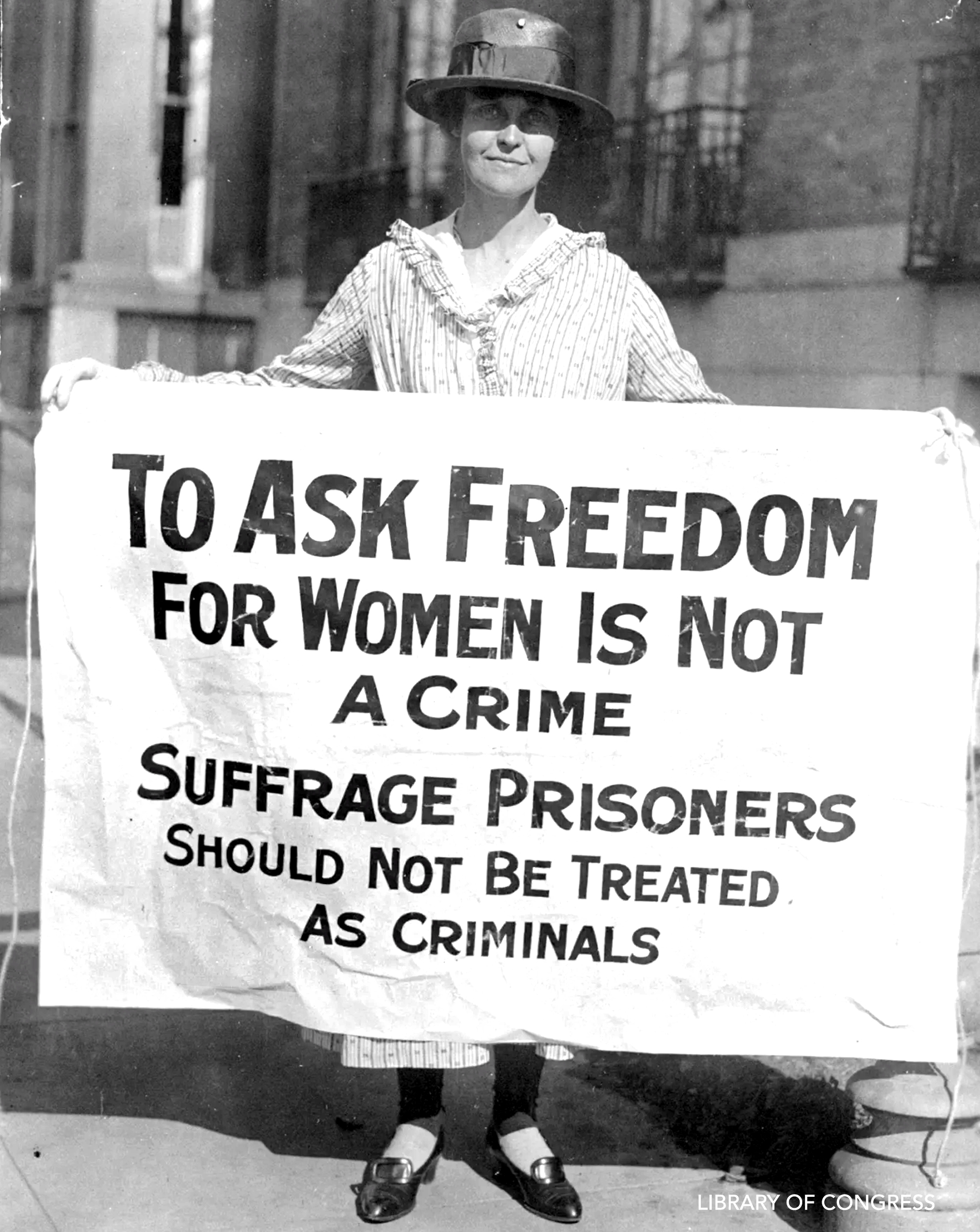

As members of the National Woman’s Party, the women and their fellow “Silent Sentinels” had been peacefully demonstrating in the nation’s capital for months, holding banners and placards calling on President Woodrow Wilson to back a federal amendment that would give all U.S. women the right to vote.

Now, these 33 women would endure the most harrowing night in the long history of the suffrage movement.

“Never was there a sentence like ours for an offense such as ours, even in England,” Nolan wrote.

In 1913, frustrated by the lack of progress toward a federal women’s suffrage amendment, some younger members of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) decided to step up their efforts. Led by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, they organized a suffrage parade held in Washington, D.C. on March 3, the day before Wilson’s inauguration as president. Police stood by when spectators attacked the demonstrators as they made their way down Pennsylvania Avenue, and army cavalry troops eventually had to be dispatched to restore order. Some 100 women were hospitalized with injuries.

Later that year, Paul, Burns and their supporters split from NAWSA to form the Congressional Union for Women’s Suffrage, later renamed the National Woman’s Party (NWP). Both women had been involved with Emmeline Pankhurst’s militant suffrage movement in England, which used tactics such as smashing windows, heckling politicians and even committing arson. As a Quaker, Paul rejected violence, embracing civil disobedience instead.

By 1916, nine U.S. states had given women the right to vote. Though he supported suffrage on a state level, President Wilson opposed the federal amendment, and Paul and the NWP decided to aim their protests directly at him. In January 1917, right at the beginning of Wilson’s second term, women began gathering outside the White House every day, regardless of the weather. They wore distinctive purple, white and gold sashes and held signs with slogans like “Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait for Liberty?”

“The picketing strategy really unfolds over quite a long time,” says Susan Ware, a feminist biographer and author of the forthcoming book Why They Marched: Untold Stories of the Women Who Fought for the Right to Vote. “By the time you get to that November night, the Silent Sentinels have been picketing outside the White House for more than 10 months.”

At first, Wilson tolerated the women’s protests, smiling at them as he passed and even inviting them in for coffee (they turned him down). But things began to change after the U.S. entered World War I in April 1917, and the NWP chose to continue picketing the White House, even as the mainstream suffrage movement, led by NAWSA’s Carrie Chapman Catt, threw its support behind the war effort.

Amid the wartime furor, many people began viewing the Silent Sentinels as unforgivably unpatriotic. Onlookers sometimes attacked the women and ripped their signs from their hands, while Wilson himself wrote to his daughter in June that the suffragists “seem bent on making their cause as obnoxious as possible.”

That same month, police began arresting the suffragists for obstructing traffic. At first, the women were released quickly, and without penalty, but soon the courts began handing out prison time. But the women kept coming back.

“One of the things that we need to give them credit for is that they knew, after June, that when they were on the picket line they could be arrested, and they could go to jail,” Ware points out. “This was something that respectable white women didn’t usually do.”

Tensions were running much higher by August, when the Sentinels rolled out a new banner accusing “Kaiser Wilson” of autocracy, followed by three days of attacks by an angry mob and police and the sentencing of six women to 60-day prison terms. When Paul, who had stayed off the picket line for much of that summer, returned in October, she was immediately arrested and given the longest sentence yet: seven months in Occoquan.

“They’re in this kind of cat-and-mouse game with the Wilson administration and with the police,” says Ware. “The arrests keep going on, the prison terms keep getting longer, the stakes keep getting upped.”

Faced with brutal treatment by guards and horrendous living conditions at Occoquan, including worm-ridden food and filthy water and bedding, Paul and others began demanding to be treated as political prisoners. After going on a hunger strike, Paul was repeatedly force-fed and transferred in early November to the District Jail’s psychiatric ward.

The 33 women brought to Occoquan on the night of November 14 also demanded to be treated as political prisoners. Instead, prison superintendent William H. Whittaker called on his guards to teach the women a lesson. Bursting into the room where the women were waiting to be booked, the guards dragged them down the hall and threw them into dark, filthy cells.

Burns had her hands shackled to the top of a cell, forcing her to stand all night; the guards also threatened her with a straitjacket and a buckle gag. Day (the future founder of the Catholic Worker Movement) was slammed her down on the arm of an iron bench twice. Dora Lewis lost consciousness after her head was smashed into an iron bed; Alice Cosu, seeing Lewis’ assault, suffered a heart attack, and didn’t get medical attention until the following morning.

Nolan’s account of the Night of Terror, as well as pages from a diary Burns kept while at Occoquan, was later published by Doris Stevens in Jailed for Freedom, her book about the NWP.

In aftermath of the attack, many of the women began hunger strikes, as Whittaker denied them counsel and summoned U.S. Marines to guard the workhouse. But news of their mistreatment reached the suffragists outside Occoquan, as well as well-placed allies like Dudley Field Malone, an attorney who resigned his post in the Wilson administration in solidarity with the suffragists (he later married Doris Stevens).

In late November, under increasing public pressure, federal authorities agreed to release Paul, Burns and the other suffrage prisoners.

In early 1918, the D.C. Court of Appeals ruled that women had been illegally arrested, convicted and imprisoned. Within months, President Wilson had begun publicly calling on Congress to act on the federal suffrage amendment, a change of heart that was probably due not only to the NWP’s protests but also NAWSA’s more traditional lobbying strategies.

Meanwhile, the Silent Sentinels continued their protests. In early 1919, the women started lighting what they called “Watchfires of Freedom” outside public buildings, setting fire to Wilson’s speeches mentioning freedom and democracy. More women were arrested, more went on hunger strikes and were force-fed, though there were no more incidents as dramatic as the Night of Terror.

Finally, in June 1919, the U.S. Senate followed the House’s lead in passing the 19th Amendment. Over the next year, both the NWP and NAWSA worked tirelessly to win ratification in the necessary 36 (out of 48 states). On August 18, 1920, after a down-to-the-wire fight in Nashville, Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment.

Though representatives of the NWP and NAWSA were both on hand in Nashville to celebrate the long-awaited victory, the divisions in the women’s rights movement would continue long after the 19th Amendment’s passage. Still, after more than a century, the Night of Terror stands as a potent reminder of female solidarity and resistance, and just how much some women were willing to sacrifice to win the right to vote.

“They’re determined,” Ware says, recalling the Silent Sentinels on that notorious night in November 1917. “It’s pretty amazing what they were willing to go through, and what they had to endure.”

Source history.com