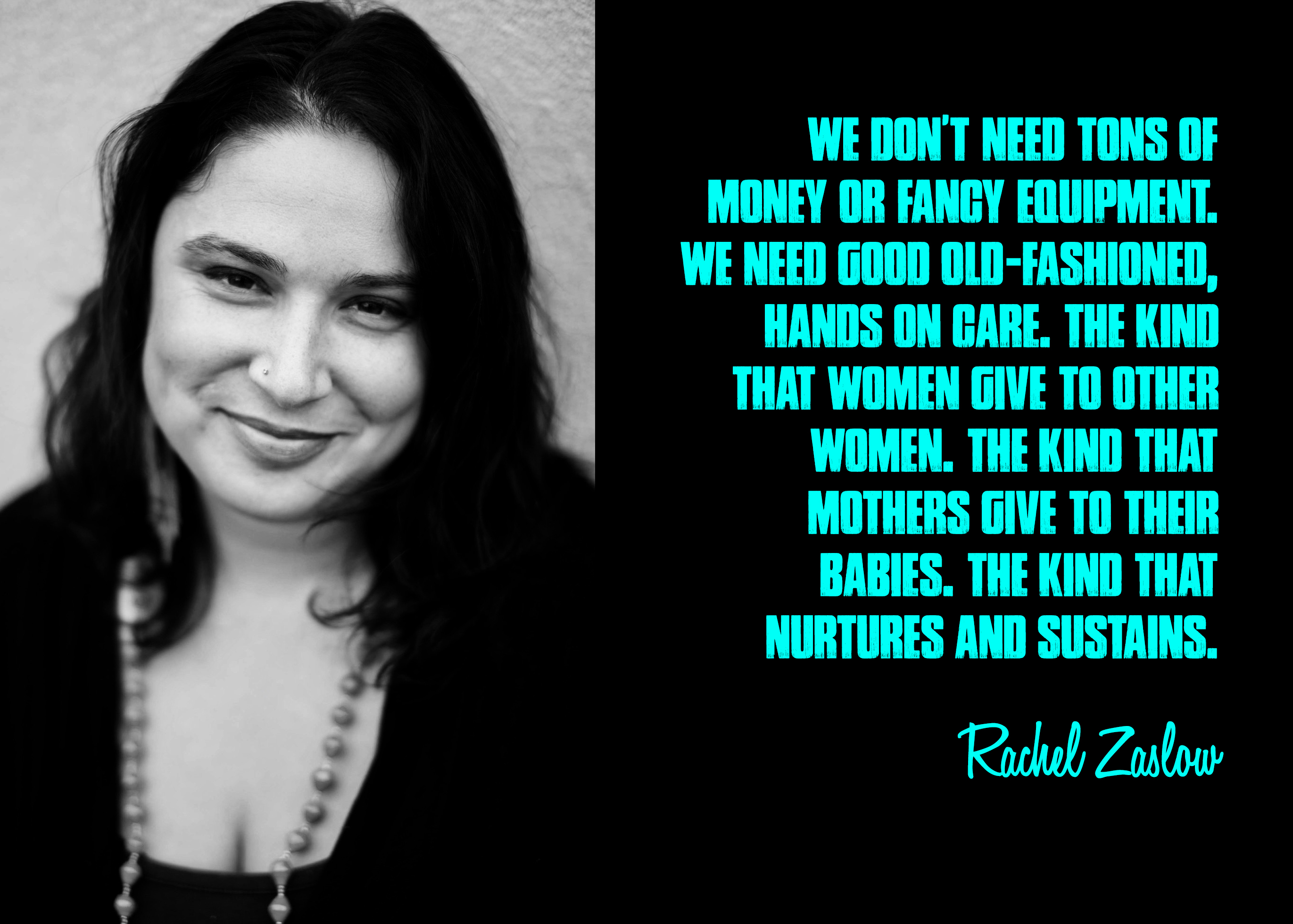

Meet Rachel Zaslow

The first mother I ever worked with who died in childbirth was 17 years old. She labored through the night at a government-funded hospital in Northern Uganda. Early in the morning, her baby became distressed. We called for a c-section but it took 9 hours for the doctor to arrive. When it was finally performed in unsterile conditions, the baby had already died, and the young woman died of sepsis three days later. At her funeral, I wept beside her mother knowing that given access to a different hospital, the outcome for this young woman and her baby would have been much different. The anger, sadness, and frustration at my inability to change the circumstances of her death have haunted me ever since.

Every minute, somewhere in the world, a woman dies in childbirth. That is approximately 536,000 women a year. 99% of these deaths occur in countries outside the West, and most of them are preventable. It’s one of the most shocking and devastating realities that most of us never think about because most of us never have to. Imagine if instead of listening to ‘hypno-babies’ and preparing playlists for your birth, you spent your pregnancy believing you might die. Now imagine having a baby and that fear of death every few years for most of your reproductive life. Women are dying all around the world and the international solutions generally fail miserably because they do not take into account the complexity of women’s situations. When women cannot control when or with whom they have sex they cannot avoid multiple pregnancies in a short amount of time. When women live 20 miles from the nearest health facility, they end up delivering alone at home or along the side of the road while trying to get help. When women do reach hospitals they are often so overcrowded that mothers in labor are turned away or are treated violently by staff midwives for not pushing fast enough or failing to bring their own piece of plastic to give birth on.

As I began to understand the layers of complication that women face when giving birth in really hard conditions, I also began to truly understand (in ways that my privilege had previously blinded me to) that the solution to any problem has to come from its own community. NGO’s that bring in solutions to the maternal health crisis tend to be focused on one aspect but fail to understand the bigger complex picture within a community. This is why we founded Mother Health International (MHI). Our Birth Center in rural Northern Uganda was built in 2007 by a collective of local traditional midwives as a response to the crisis of maternal and child health after 23 years of war, rape and trauma. Together we envisioned a space where women could come to give birth and be treated with respect, with one on one attention, with access to emergency transport and medicine.

We envisioned a locally sustained clinic where women didn’t have to pay to receive services but could work in collectives on projects like gardening or sewing with the proceeds of the projects going back to maintain the clinic. We envisioned a transport arrangement that would pick women up in labor to avoid them birthing alone on the side of the road while walking miles to seek help, and we envisioned the same transport driving them home post-partum to avoid hemorrhage. We named our clinic ‘Ot Nywal Me Kuc’ (House of Birth and Peace in Acholi), because after 23 years of war the ability to give birth safely is in and of itself an act of restoring peace to the community. I wept when we opened the doors to the House of Birth and Peace, recalling that first mortality I had seen in the hospital years before, and knowing we were part of paving a better way for women.

I am proud to say that in ten years and over 8,000 deliveries we have never lost a mother. We have turned perinatal mortality around in one community. We went from only 30% of women having prenatal care, to almost 96%. We went from an infant mortality of 64/1000 to 11/1000. Every single mother who has walked through our doors has also walked out. The impact of this is immeasurable. Children have mothers to care for them, feed them, send them to school, advocate for them and love them. Perhaps more subtle, but no less important, is that women in our community don’t fear dying when they become pregnant because they know they have a safe place to come. They come for prenatal appointments with smiles, they often stay to take a nap afterward and then leave with vegetables, fruits and herbs from our gardens; they labor with midwives attending to their emotional and physical needs, knowing that if anything happens they will be cared for. They are mothered.

There is no one answer to the myriad of violence and injustice that women face while giving birth, but one thing I know for sure is that one-on-one care and community-focused support is not only achievable, it is imperative to good outcomes. I think this is milestone one. Now we need to be able to leverage this success to work with more groups of midwives and women. African women have the answers. We don’t need tons of money or fancy equipment. We need good old-fashioned, ‘hands-on’ care. The kind that women give to other women. The kind that mothers give to their babies. The kind that nurtures and sustains. And we need to do it together.

Click here to learn more about Mother Health International.