Making a difference in women and girls lives

In Kitui, Kenya we combined our approaches to maternal health and WASH to significantly improve the health of a community in need. To increase access to drinkable water, we trained water artisans, all of whom were women, to build and maintain not just one type of water infrastructure, but several types including: conventional wells, giant wells, boreholes, sub surface dams and rain water harvest tanks for the entire community to use. We also installed water tanks, hand washing stations and latrines at five health facilities in the district. Prior to the project, women who came to deliver their baby at the health facilities were forced to bring their own water because the health facilities did not have access to water on site. This caused most women to deliver their baby at home and to not attend check-ups during their pregnancy, increasing both mother and baby’s risk to complications like deadly infections during childbirth.

Read the stories of real people who have had their lives changed by Amref Health Africa:

In rural communities in Africa, some health facilities are so under-resourced that helping mothers give birth by the light of kerosene lamps, candles – and even the light from a mobile phone – is not completely unusual for a midwife. Take it from Mary Leonard Raphael, a midwife in Tanzania, which has one of the highest rates of maternal mortality (398 women die for every 100,000 live births): “Once, I was helping a mother deliver her baby in the middle of the night when the power went off. She was already in labor, so I had to keep going using only the light from my mobile. The lights might go out, but we’ve still got mobile phones. I had to keep pressing buttons on my phone just to illuminate the room. To complicate things further, the colleague who was helping me had to rush off and help another woman in labor. The baby became very tired and I had to resuscitate him when he arrived. Thankfully, both he and mother came through. Unfortunately, most women in Tanzania do not get to deliver their babies with a midwife like Mary, placing themselves and their children at a higher risk of complications, including death. This is why Amref Health Africa works to train more midwives and other health workers to prevent these needless deaths; midwives like Mary, who has always wanted to dedicate her life to saving mothers and their babies: “Being a midwife is all I’ve ever wanted to do. As a girl, I loved children and was fascinated by pregnancy. The first time I helped deliver a baby was frightening, though – all I knew of birth was what I’d heard from the labor wards and I got quite a shock. Luckily, the birth wasn’t complicated – which made it less traumatic for the mother, and for me too. That was 12 years ago. Since then, I’ve helped deliver hundreds of babies.”

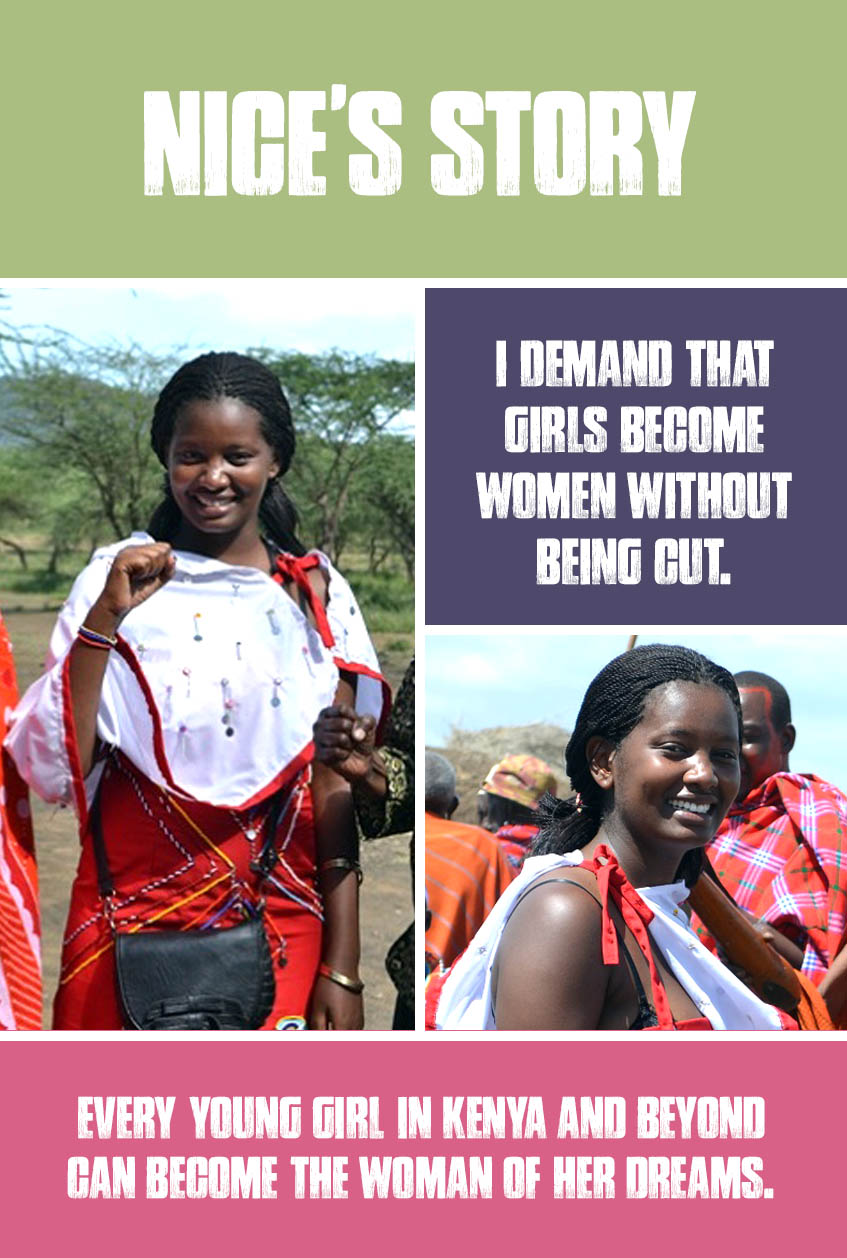

Growing up as a Maasai girl was not easy for me. To be honest, it’s a man’s world. Girls and women are to be seen, but definitely not heard. We are a proud people…proud of our traditions and our identity. Yet, in the process of preserving our culture, we have embraced a system that denies women basic human rights: the right to control her body, the right to an education, to choose to whom and when to marry, and the right to express an opinion. Female genital cutting, although illegal, is commonplace. Girls as young as 10 or 12 are being cut, taken out of school, and married. I too, would have been one of those girls. If it were not for a series of events that changed my life. When I was only eight years old, my world was shattered when my parents were devastatingly ripped away from me. Whispers and rumors hinted at a mysterious disease. But I was told nothing. I was eight years old and my life had changed forever. Everything I knew was gone. My home, my security. But, surprising as it may seem, every dark cloud has a silver lining. Not belonging to a family actually offered me an escape from forceful genital cutting. Sure, my Uncle tried to organize it, to literally beat me into submitting to the cut, but I resisted. I ran away. I listened to that spark of determination that had already started burning in my heart.

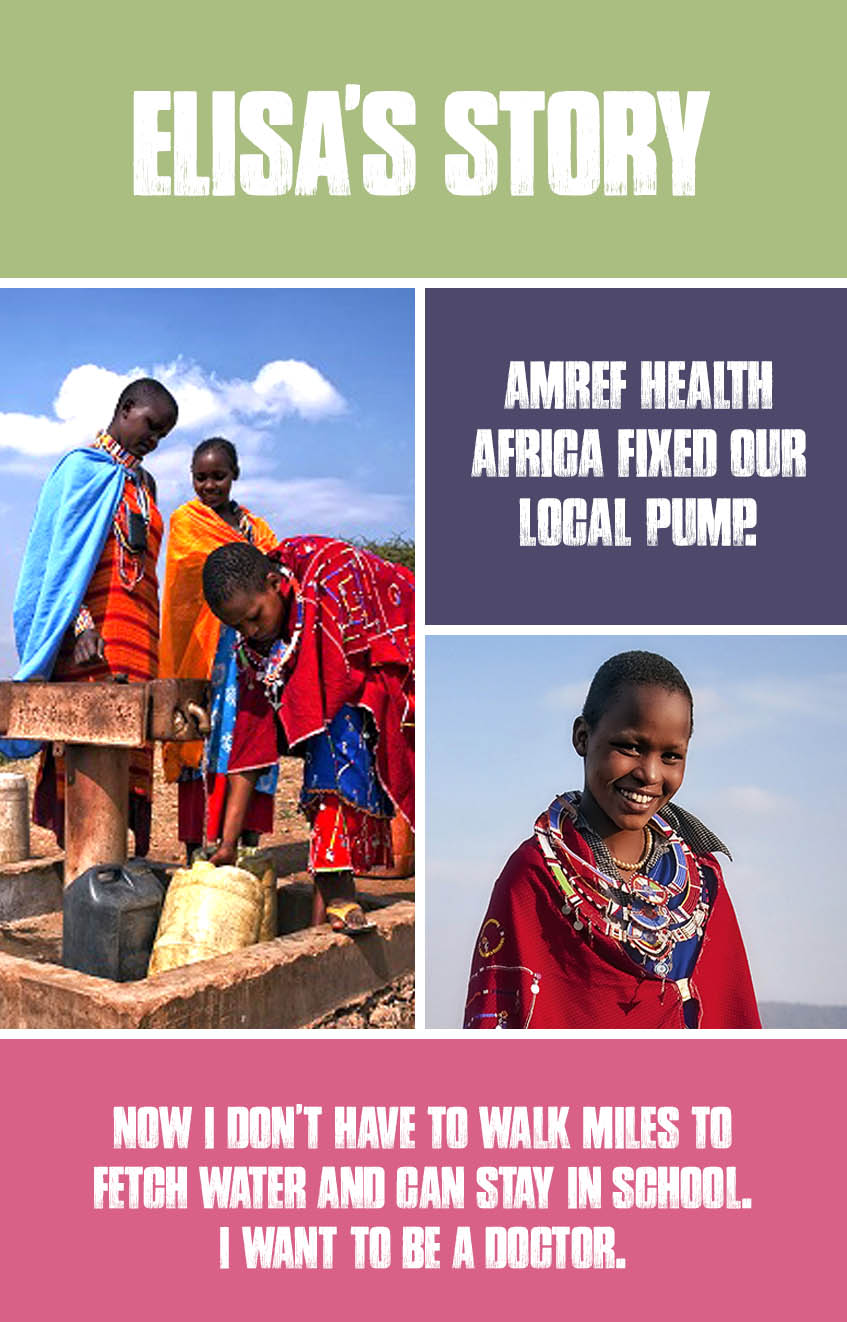

It doesn’t rain much here in my village of Oikiloriti in southern Kenya. There are no permanent rivers, so each day is a big challenge to find enough water for washing, cooking and our cattle. My name is Elisa. I am 13 years old and a member of the Maasai, a nomadic tribe who live in southern Kenya and northern Tanzania. My day begins at 5:30am when I wake up to a gurgling sound, as my mother fills a jerry can with our morning water for bathing and breakfast. I get out of bed, wash up, get dressed and help with breakfast. I live in a mud hut in a ‘boma’, a little village of huts surrounded by a fence made of thorn branches. Of course we have no water taps at home, so we must go and fetch water from the nearby community water source. As I get ready for school, my mother loads the donkeys with empty jerry cans. On school days, she gets the water, but on weekends, it’s my chore to get it with my older sister-in-law and the donkeys of course. I’m not allowed to get water alone – it’s too dangerous. I remember when it was so much harder to get water. I had to spend hours every day fetching water from the small far off lakes. And the water wasn’t even clean – often it actually made us sick. I remember at that time that our ugali, the white Kenyan maize porridge, was always very brown from the dirty water.

Source: amrefusa.org